Many years ago when I was a tiny baby making InFlux (of which there is now a Redux), I had no idea what I wanted to do with it narratively, if anything. Because, from a young age, he had humoured me, I emailed Gabe Newell about it, knowing he was in the habit of either replying or forwarding to someone he thought might reply. I got some good thoughts back from David Speyrer, who’s been at Valve since ’99, which I shall publish here now because at a party last night someone was interested.

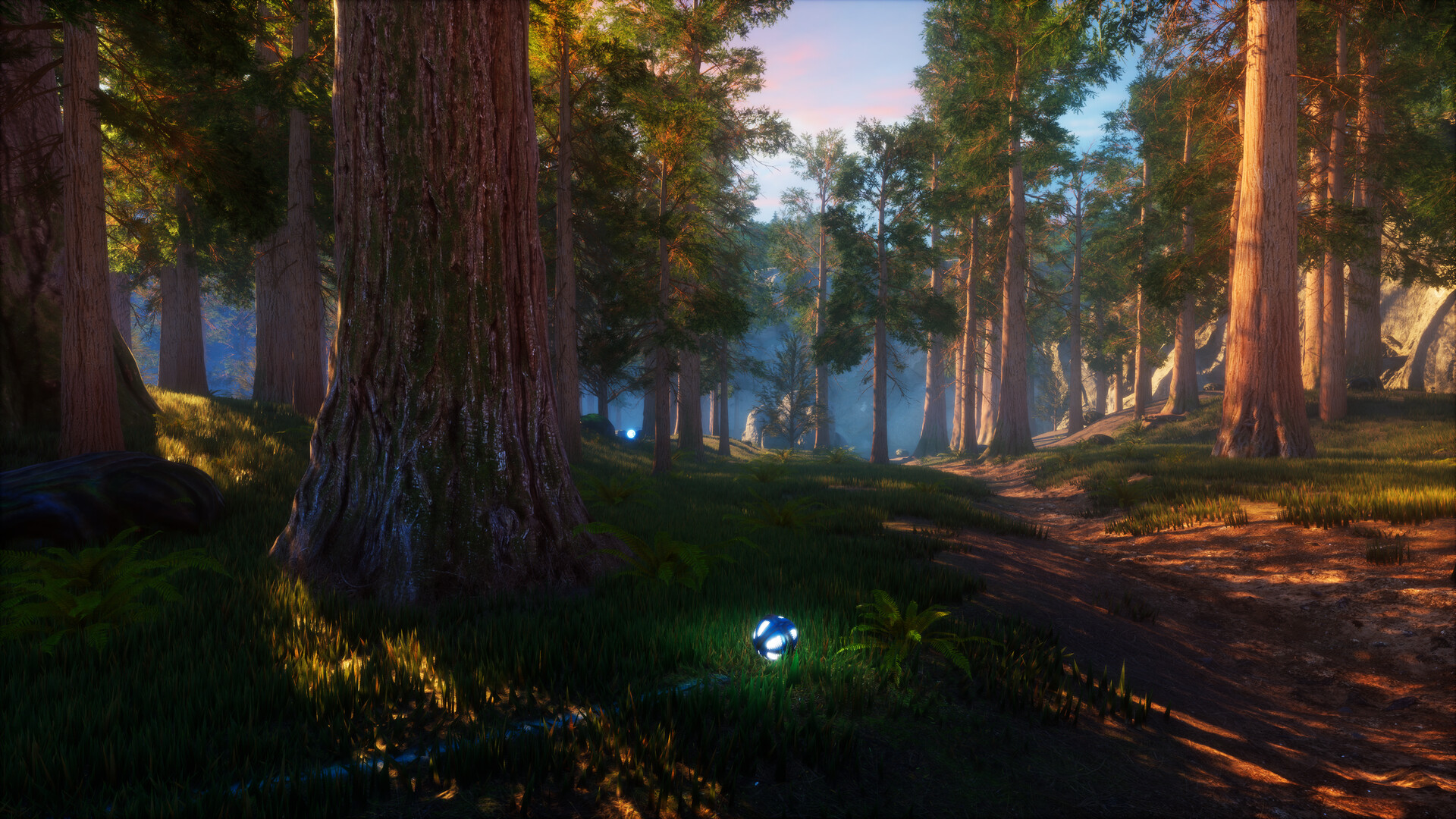

The state of InFlux at the time was that it had been a simple sequence of puzzle rooms, and some folks thought it should stay like that, but I was observing puzzle fatigue (a term I had learned from Valve’s developer commentary) that I had thrown in lower-engagement “overworld” sections as a solution for. That made it feel like it had to lead somewhere, have some sort of narrative, and I didn’t have one. There was just enough to the overworld, though, that players were inventing narrative elements that I hadn’t thought of suggesting, and I had started reacting to that by planting evidence to support people’s interpretations.

For example: I had added torches lighting the way between puzzles, which had people wondering (ahead of me) who lived on the island. So I added huts and little villages. Just because it looked nicer, those had campfires with glowing embers, which suggested to people that the villagers had just left, so I added a bit where you could see some canoes leaving the island in the distance. Someone thought the puzzle rooms, which I had just dropped on the landscape, must have been there for centuries and were only now coming to life, so I grew moss over them in places and made them light up when you completed them. This felt like a good way to fake a story when I had no budget for one, but it also felt cheap, I hadn’t much confidence in it, so I wanted thoughts from smarter people.

Anyway, here’s what I got from David:

Gabe asked me to check out your video. It took me inexcusably long to get to it, I’m sorry to say.

Anyway, we’ve found that narrative can serve several purposes in a game: it can serve as a refreshing reward for forward progress, it can make the player’s in-game actions matter in a larger context, and it can artfully tell the player what to do next. Of course it should always entertain and try to evoke an emotional response while doing any of these things.

In your game, if players start to feel like the puzzle solving becomes a monotonous grind, or if they feel like they’re solving puzzles for no particular reason, then maybe some story is in order.

Your idea of creating a completely enigmatic plot from your players’ theories is an interesting one. If you try it I’d love to hear how it turns out. Normally we keep the untold parts of our stories as a “possibility space” – we have a few different ideas for what the real story might be and, when need to, we can pick between them, but there’s no reason to commit until we have to. I think (hope) our players sense that underlying craft and structure beneath what we do tell and appreciate our stories more because of it.

This felt, I suppose, quite validating and focusing at the time. I was maybe 21, and I don’t think I’d thought properly about it at the time, but I had sensed that loosier-goosier approach in Half-Life, and it helped me, I think, to have it slightly unveiled like this. I suppose I had had, dropped into my mind mostly unquestioned, the gamer collective wisdom at the time that there was always a Story Bible or ground truth to these things; that if something was gestured at vaguely in a game’s story it meant there was a static truth the author could casually tell you if they wanted, which of course is rarely the go, but I was a baby.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.