Some years ago I did a quest scripting tool for an ill-fated open-world game I was contracting on. It was ages ago now, the project’s concluded, and nothing here identifies any of it, so I’m sure nobody’ll mind if I talk about my approach a bit here.

My number one concern when creating tools for designers, especially on a larger team, is to minimise the need for interaction between design and engineering in a way that’s comfortable and safe for all concerned, because even in a (rare) best-case social and technical scenario, if designers need to go through engineers to pursue ideas, those ideas will mostly just not get pursued.

Quest systems and level scripting systems are both pretty interesting and potentially hairy problems to solve. Ideally you know more or less what the game is going to be when you start these, but that was not the case this time. I described a situation in my post about Weird West’s crafting system where the desired outcome was similarly murky, but that was in a fun way – the ex-Arkane folks (principally Julien Roby and Raf Colantonio) understand the benefits (and risks) of taking a freeform approach when you can. The task I was set for this project was vague in the other way – the game had not been designed, and folks were kidding themselves about that at the time, so there were many wrong answers but no right ones.

My approach was the same, though – I tried to build a system that would gracefully accommodate all the things I suspected designers might end up wanting to do, while trying not to create a situation where the tools would end up dictating the design.

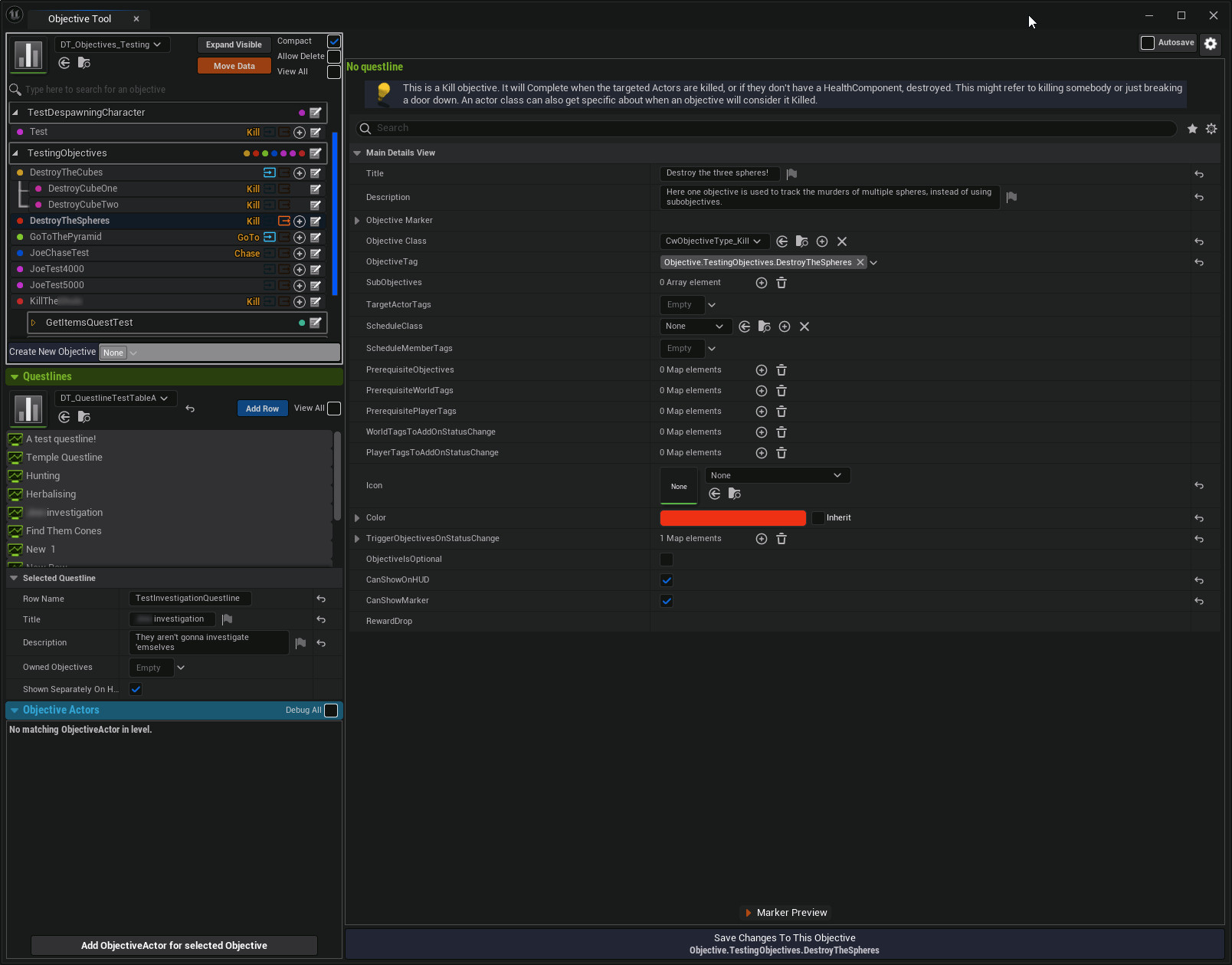

Here’s what the tool looked like with all panels expanded:

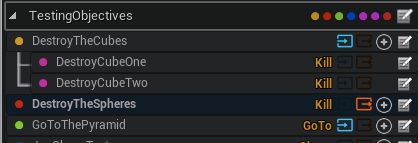

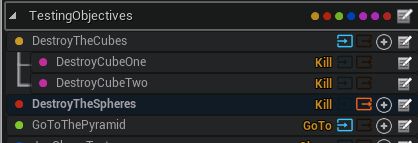

The tool used Data Tables to store quest data, because I found it to be organisationally convenient (often it isn’t, compared to Data Assets, but here it made sense to lump groups of quests together into one file). The user never has to deal with Unreal’s data table UI, though, because the tool aggregates the data from all tables (or the selected tables) and presents it in this UI. It’s also easy to move a quest from one table to another. Quests and subquests were the same thing, just “nested” in each other by tag reference, and the UI would present them as a tree.

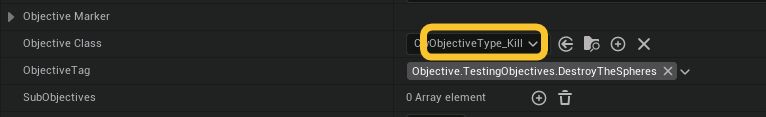

I wanted to avoid requiring designers to write code, but also wanted to be sure they were allowed to write code. ObjectiveType was a UObject that you could subclass to create broad-strokes objective logic, mostly verbs like kill, get, chase. Designers would string these together as sub-objectives within a quest to create a wide range of behaviour just by tweaking parameters, but if they needed to, they could create their own subclass in Blueprint to do something properly bespoke. As long as that doesn’t end up happening all the time, this “build quests out of prefabbed behaviour blocks” approach has a lot of benefits. If there’s a bug in one kill quest, it’s technically in all of them, so fix it once and it’s fixed everywhere.

As many have observed before, there aren’t, boiled down, that many things you get told to do in a video game. It turns out you only need, like, four of these to get almost all the quest behaviour you see in most open-world games – chase and go to and escort and race and flee from and protect are all the same code; we’re just triggering different events based on different distance thresholds from an arbitrary object, and falling back to some state (success, failure, canceled) if the target dies or whatever.

All of this was target-agnostic. Kill would bind to the target’s HealthComponent and trigger if it died, or if there wasn’t one, it would use OnDestroyed, so Kill could be about an assassination or just breaking a crate. Quests were identified by GameplayTag and could have other quest outcomes, world tags, and player tags as prerequisites, meaning a designer could add a trigger anywhere in the game to start the quest KillPaulieWalnuts and not worry about whether Paulie Walnuts was already dead – the checks all live in the quest data. This also meant that the objective system was always “compatible” with all other systems, in the sense of neither knowing about them nor requiring that they know about it (the best sense). I try to build all my systems this way.

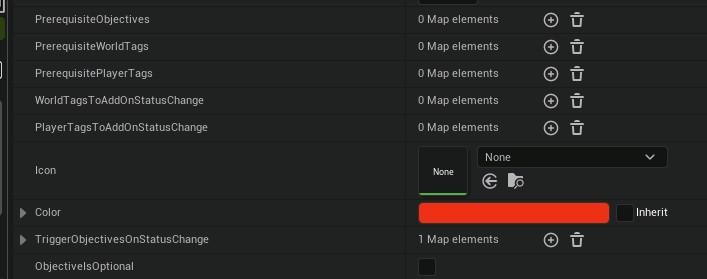

Quests could also trigger each other, and I added these little i/o icons on each quest in the outliner to flag whether they did this or not. Quests could also add or remove tags from the player and/or the world per-quest-event (start, complete, fail, cancel, conclude), so it was easy to say “quest A can only ever happen if quest B was canceled and it’s raining” or whatever. As a result, it was easy to set up branching questlines – my examples were all starting with a vague objective like “get inside the building” and branching into multiple multi-step approaches which would all auto-cancel when you succeeded at one of them.

The way that the rubber of this quest data hit the road of the game and levels was via ObjectiveActors placed in the world, which would (optionally, as opposed to just using tags) let the user tag specific objects as related to a quest. I had a lot of toggleable debug vis in the editor viewport to show how actors related to one another and to objectives, which I can’t show because that’d be showing the game. Also not shown here: there was also a Marker Preview function which let you see what the quest markers would look like in the game UI straight from the tool, saving a lot of testing.

I was not on this gig for too much longer after I made the tool, but while I was there it was received well. I’m not sure if it was ever battle-tested enough to reveal issues, but I still think the approach is sound. Tools like this are about empowering designers to go nuts creatively, while preventing technical complexity from increasing as a result, and from that perspective this tool was a banger. I’ll probably do it again.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.